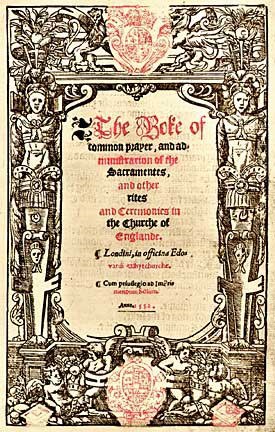

1552 Book of Common Prayer

When Henry VIII died in 1547, worship in English was not significantly different from in any Catholic country in Europe, other than in eschewing all reference to the Pope. There had been some reduction in the number of saints’ days celebrated, and the dissolution of the religious houses, but doctrine, as summarised in the Act of Six Articles of 1539 was Catholic. In particular, the doctrine of transubstantiation – that the body and blood of Christ were truly physically present in the bread and wine of the Eucharist was maintained.

With the accession of Edward VI, men came to prominence who had moved further towards Protestantism – and generally to a Calvinist interpretation, rather than Lutheran. Lutherans believed in the Real Presence of Christ in the bread and wine, whilst Calvinists saw the bread and wine as symbolic.

One of the proponents of further reform, who had hidden his true beliefs under Henry, was Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury. He wished to move the English Church towards the Reformed Faith, but there were political difficulties.

First, the vast majority of the population remained Catholic, and would be unlikely to accept wholesale change if it were brought in too quickly, and second, as the King was under-age, it was debatable whether religious change could be made during his minority. It was not clear whether the King’s position as Supreme Head of the Church in England, could be exercised by the Protector and the Council, or could only be exercised by the King personally. The latter view was propounded by the Catholic Councillors, particularly Bishop Gardiner of Winchester, before he was removed from the Council, and by the King’s heir, the Lady Mary.

An early step to reform was the introduction of the Book of Common Prayer of 1549. This work, which outlined the order of prayer for the English Church, was largely the work of Cranmer and was not radically different from the Catholic ritual – other than being in English. It was based on the Latin Use of Sarum (as amended in 1542) – the most prevalent liturgy in the province of Canterbury, as well as the breviary of the Spanish theologian, Cardinal Quiñones, and the work of the Archbishop of Cologne, Herman von Wiedd. Much of the ceremonial of the Catholic Church was retained, including the wearing of vestments.

For the more radical clergy, the 1549 Book did not go nearly far enough. Bishop Hooper of Gloucester claimed that it was ‘very defective…in some respects manifestly impious’. This was a view shared by the European Reformers in England – Martin Bucer and Peter Martyr, who were Professors of Divinity in Cambridge and Oxford, and John Laski, who was Superintendent of the Stranger (foreign) Churches in London.

By 1550, other members of the government (now led by John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland) were also open to further reform, and a new Prayer Book was proposed. Little is known about when this was commissioned, but it was implemented by Act of Parliament in April 1552. From 1st November 1552, it was to be the only legal form of service in England.

Cranmer, either because he had been biding his time, or because the objections to the quasi-Catholic nature of the 1549 Book had convinced him he had not gone far enough, included additional elements and dropped other parts. The most significant alteration was in the wording surrounding the Eucharist, to render it more ambiguous as to the nature of the bread and wine and their relationship to the body and blood of Christ.

The practice of kneeling to take Communion was retained. This was enough to displease the more ardent reformers. In a series of sermons preached before Edward VI in the Lent of 1552, there were numerous criticisms of the Prayer Book. The most outspoken critics were Bishop Hooper, and John Knox. Knox, although Scottish, was a minister in Newcastle. He had come to the attention of the Duke of Northumberland, and had been invited to take part in the Lent sermons. As was his wont, he thundered against anything that smacked of ‘papistry’.

King and Council were impressed by Knox’s criticisms, and, after some deliberation, sent an order to the printer to cease production. They intended that the rubric requiring Communicants to kneel, should be removed. The Council then instructed Cranmer to revise the rubric. Cranmer was outraged. He wrote to the Council, making two points – the first, that no individual could change the Prayer Book as approved by Parliament, and that, second, Knox and the other radicals were ‘unquiet spirits which can like nothing but that is after their own fancy, and cease not to make trouble and disquietness when things be most quiet and in good order.’ He absolutely would not remove the requirement to kneel.

Unable to face Cranmer down head on, Northumberland invited Knox and others to make written comments on the Forty-Five Articles of faith (later reduced to forty-two and then the current thirty-nine) being prepared as the summary of doctrine for the English Church. Knox took the opportunity to attack kneeling.

The Council came up with a compromise. On 22nd October 1552, they added to the rubric, the statement that kneeling was to show gratitude to God, for the sacrifice of Christ, and not to imply any adoration of the bread and wine as His body and blood. Because the Prayer Book was to come into universal use by 1st November, this additional rubric had to be printed in black as there was not time to print in red, the usual colour.

This ‘black rubric’ was one of the items dropped from the 1552 Prayer Book, when it was reconstituted under Elizabeth as the 1559 Book of Common Prayer, which became the only permissible order of service until the Commonwealth period.

Note: The arguments and counter-arguments of the Reformation are complex, abstruse and hard to condense into a short article. If we have misrepresented any doctrine in summarising it, we apologise.