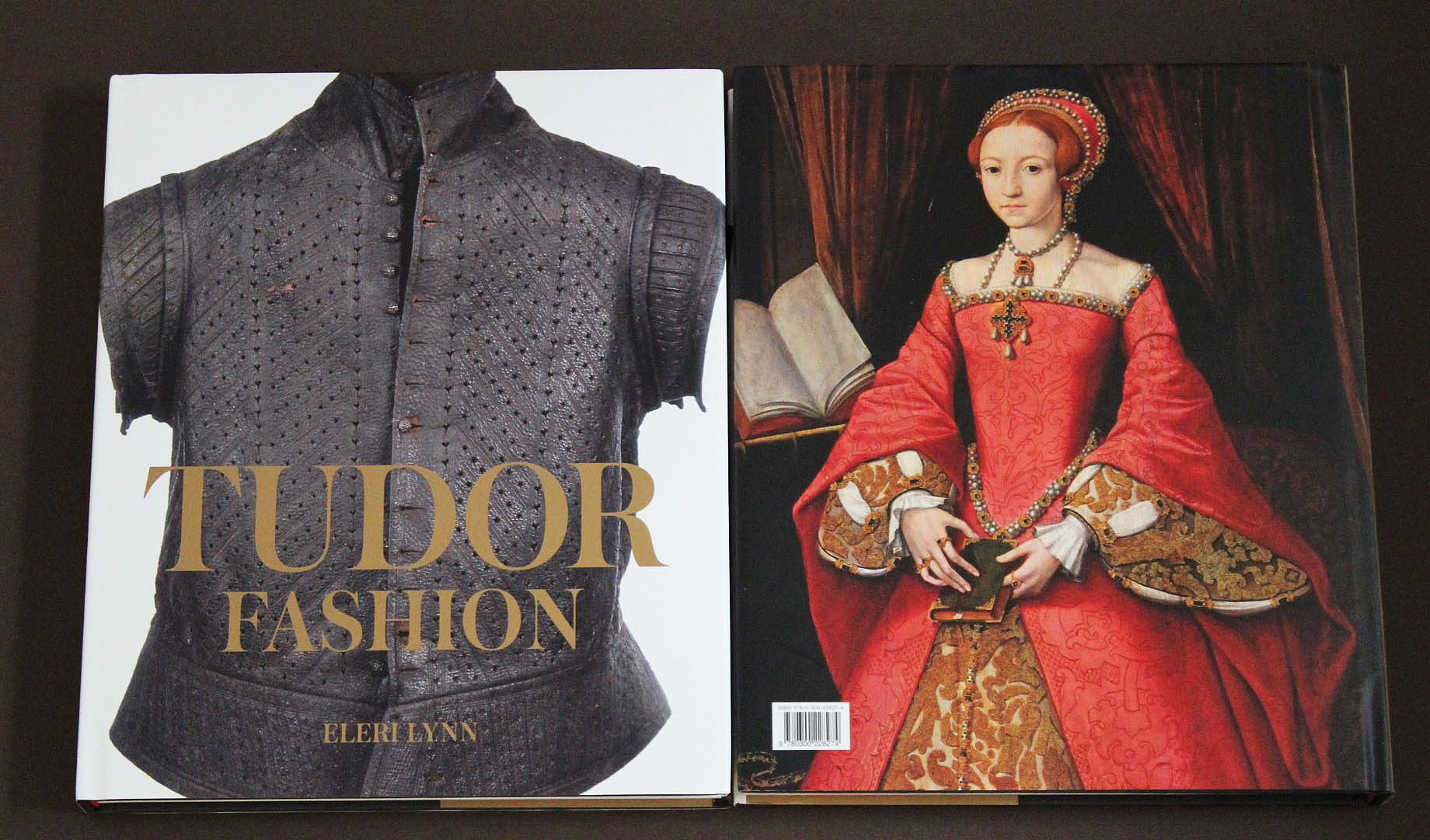

Tudor Fashion

with Eleri Lynn

Eleri Lynn, fashion historian and curator responsible for the dress collection at Historic Royal Palaces, talks about Tudor fashion, and how dress was used as a means to communicate status and power in the courts of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I.

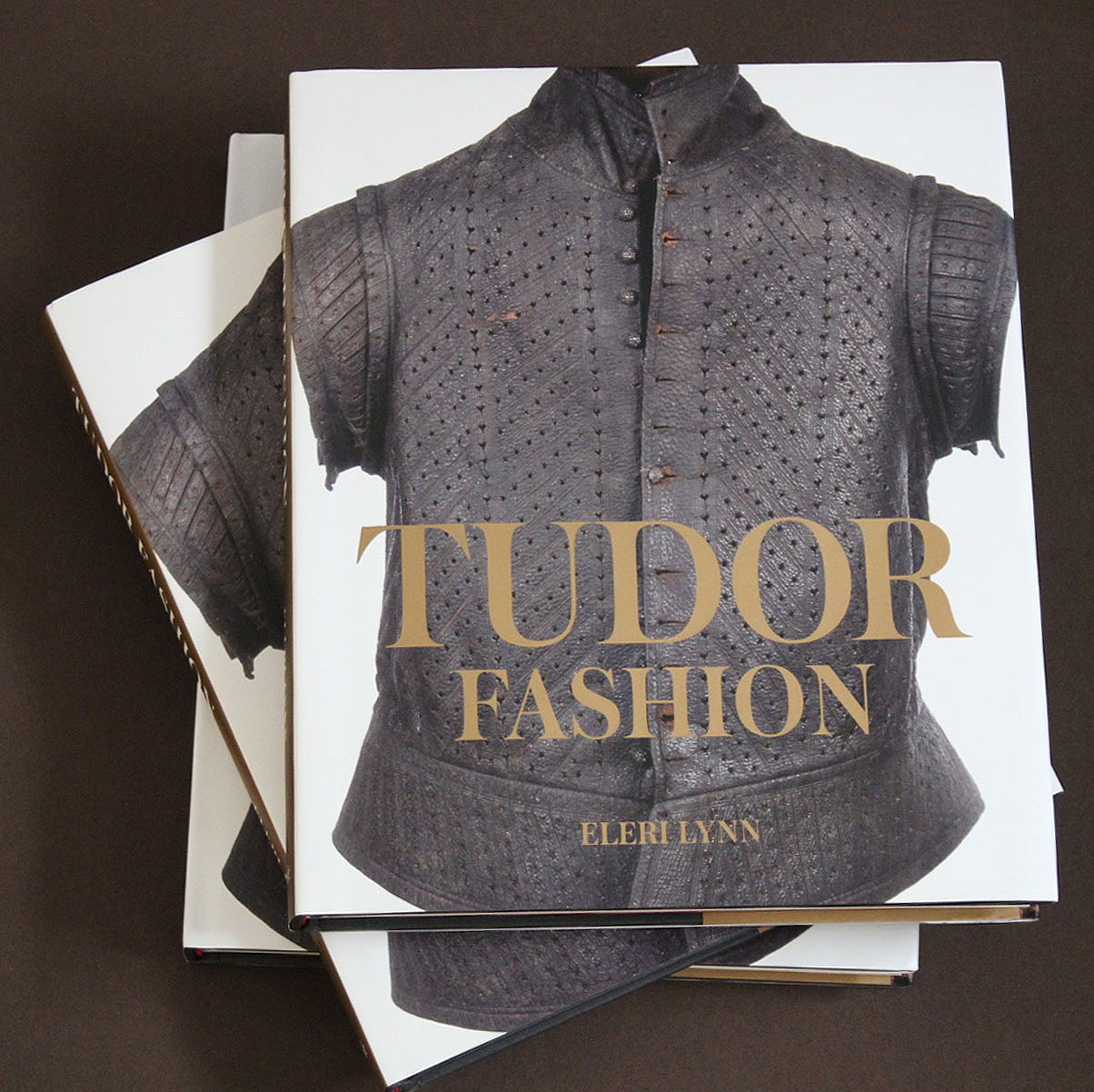

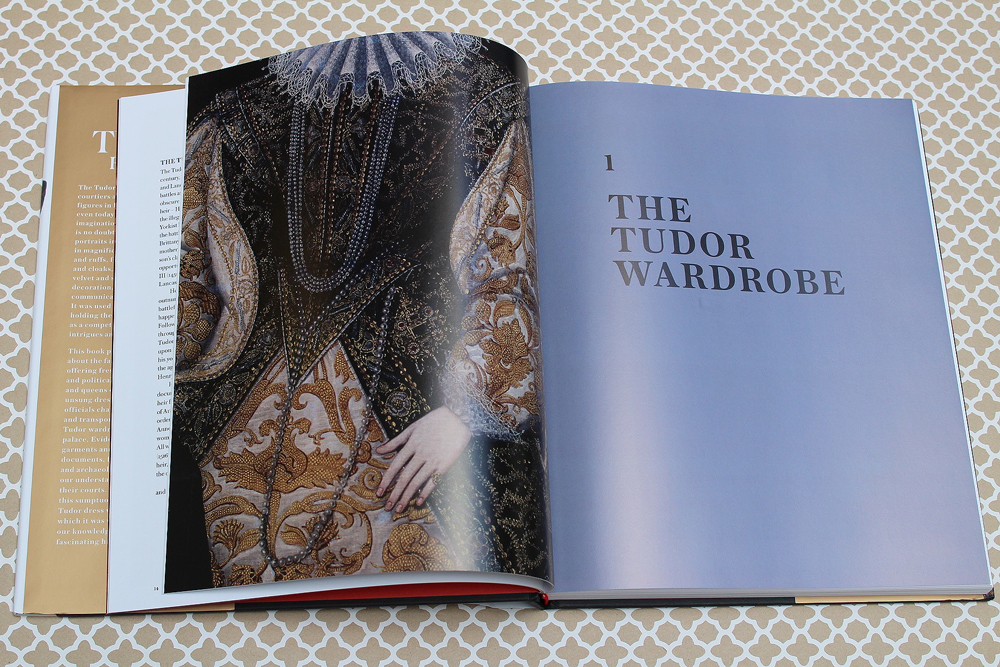

Eleri’s book, Tudor Fashion, presents new research about the fashions of the Tudor dynasty, offering fresh insight into their social and political milieu. Histories of Kings and Queens complement stories of unsung dressmakers, laundresses, and officials charged with maintaining and transporting the immense Tudor wardrobes from palace to palace.

Q: Your book Tudor Fashion focuses on the historic dress of the Tudor dynasty. What was the principal role of dress at court?

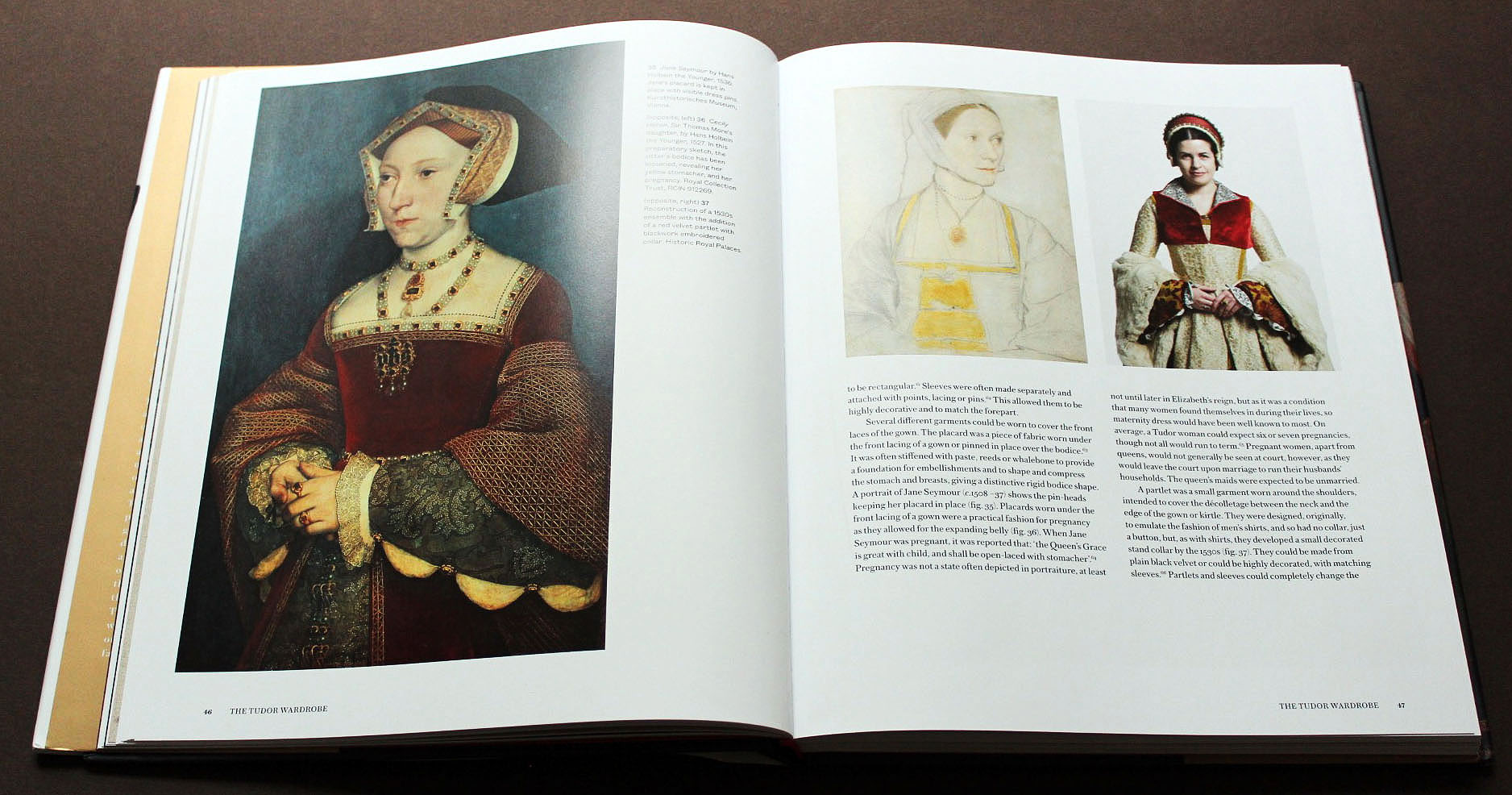

A: Well, for me it was interesting to see how much of the Tudor story can be told through dress, from the political to the personal. Henry VII used dress to bolster his claim to the throne and project a status that many doubted that he had a right to, spending millions of pounds in today’s money on a new wardrobe in the days after the Battle of Bosworth. Katherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn used dress as a weapon in their rivalry for Henry VIII, arguing over who should make Henry’s shirts, who should claim the Queen’s jewels and who should dress most regally. And the young Princess Elizabeth used modest dress to protect herself when threatened by her half-sister Queen Mary, deliberately dressing down so as not to be seen to rival her sister.

The importance of dress can be weighed by the fact the Tudor monarchs themselves invested huge proportions of their wealth in the creation and maintenance of their wardrobes and took great interest in the way that they presented themselves – particularly when threatened or faced with rivals.

Q: How did the fashion at Elizabeth I’s court differ from that at Henry VIII’s court?

A: There were significant changes in fashion between Henry VIII’s reign and that of his daughter, Elizabeth. One of the main changes came about because Henry inherited a vast treasury which he went on to deplete, meaning that Elizabeth had to be very frugal. Henry hardly ever wore the same thing twice and spent eye-watering amounts on his clothes. Elizabeth often recycled her clothing, regularly sending dresses to her tailor and embroiderer to be adapted and updated, to make old dresses look like new. The other change of course is in the fashionable silhouette – it is interesting to reflect on just how much space the fashionable male frame took up during Henry’s time and how that was pretty much reversed during Elizabeth’s reign. The wheel-farthingales and ruffs of the fashionable female, much like the Queen herself, dominated space at the Elizabethan court. Also, there was a lot of male leg shown at the Elizabethan court and I do think of it a little like a peacock court, with her male courtiers putting themselves on display to catch the Queen’s attention.

Q: The ‘Armada Portrait’ of Elizabeth I is back on public display in the Queen's House at Greenwich after a period of restoration. The splendour of her costume is striking, for example the embroidered suns on the skirt and sleeves. Could you tell us more about the symbolism of Tudor costume?

A: The use of symbolism had developed throughout Elizabeth’s reign, both as a means of showing loyalty but also as a conscious device to mythologise her. She had always worn a vast number of pearls, as they represented purity. However, a more complicated language of symbols seems to have taken hold at court around the mid-1580s when England was under threat of invasion from Spain. Symbols became a helpful way to praise the Queen, especially when translated into jewellery.

Elizabeth received eighty such symbolic jewels as New Year’s gifts in January 1587. One of the most popular emblems was a crossbow, which denoted strength and purpose. Other symbols include the serpent for wisdom, an arrow for martial loyalty, a pelican for piety, spires for the direction to heaven and rainbows for the celestial.

Elizabeth also encouraged a court culture where elaborate rituals of courtly love were played out with her male courtiers. She received gifts of symbol-laden jewellery that was often used as a device for flirtation. She called the Robert Dudley, the Earl of Leicester, her ‘Eyes’, and he consequently gave her a ring of gold, agate and rubies made like two eyes.

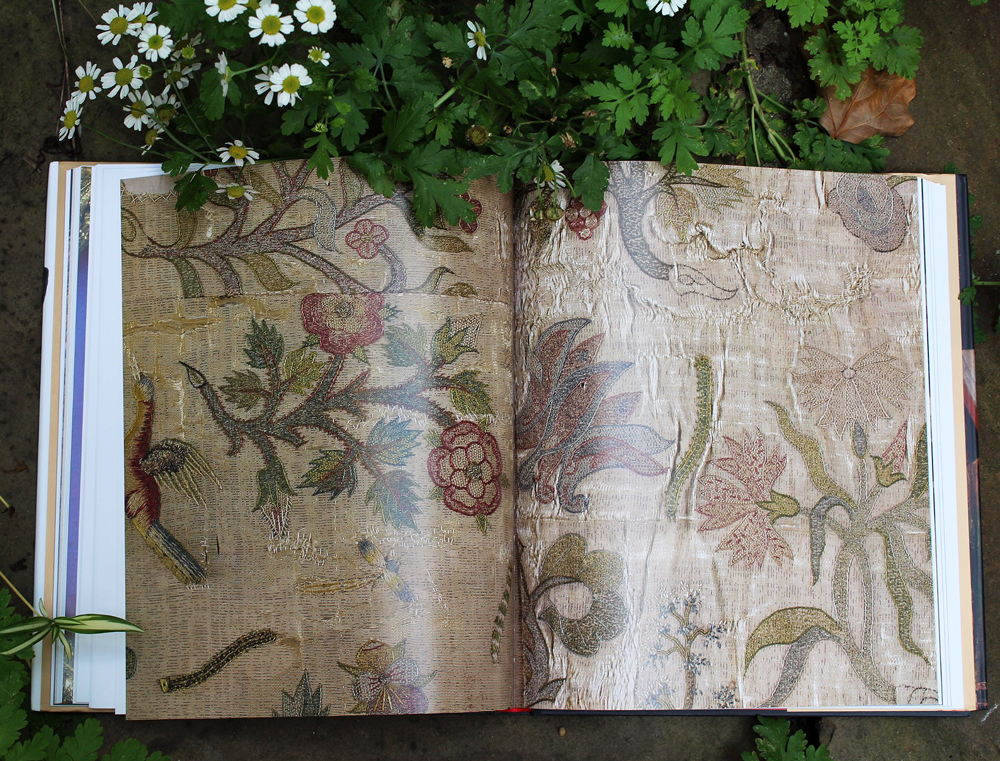

Q: Last year you identified an altar cloth from Bacton as originally belonging to an Elizabethan court dress, possibly to the Queen herself. How did it make you feel, coming across this fabric considering how rare the extant Tudor textiles are?

A: Seeing the Bacton Altar Cloth in situ at the Church of St Faith, Bacton, was quite something! It was clear that I was looking at something very special – late sixteenth-century cloth of silver embroidered all over in silk and gold and silver thread, showing evidence of having previously been a garment or dress. The cloth’s status stems from its connection to Blanche Parry (1508-1590), a native of Bacton, who was Chief Gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber and almost lifelong companion to Queen Elizabeth and also regular recipient of gifts of dress from the Queen’s own wardrobe. All the evidence seemed to point one way – that this was an elite court garment from the late Tudor period and indeed, given the materials and connections, might be the only survival apart from accessories from Elizabeth I’s own wardrobe.

The cloth is now on loan to Historic Royal Palace and is currently receiving the finest conservation care at Hampton Court Palace. We hope to research it further and put it on display in next year or so.

Q: You mention in your book Henry VIII’s law – ‘An Act against wearing of costly Apparel’. How did this dictate the dress of ordinary people like craftsmen and merchants?

A: The first parliament of Henry VIII in January 1510 issued a lengthy law entitled ‘An Act against wearing of costly Apparel’. Purple cloth of gold or purple silk was limited to the king and his direct family only. No man under the rank of lord was to wear cloth of gold or silver, hence the importance of the Bacton Altar Cloth. Crimson or blue velvet was only to be worn by a knight of the garter or above. No person under the rank of knight was allowed to wear velvet, satin or damask in his gown and doublet. Satin or damask doublets and silk gowns and coats were out of bounds to anyone who did not possess freeholds to the value of £20. Servants were not to use above 2.7 metres of fabric in a long gown and agricultural workers or labourers were forbidden to wear cloth exceeding 2 shillings per yard, under threat of three days in the stocks.

The lower orders were unlikely to be able to afford to dress above their station anyway. To put it in context, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, spent the same amount on a suit of cloth of silver as William Shakespeare did on his large house of New Place in Stratford-upon-Avon.

'Tudor Fashion: Dress at Court' by Eleri Lynn was published in the UK by Yale University Press on 4 August 2017.

This interview was first published on the YaleBooks blog on 17 November 2017.