William Cecil: Architect & Builder

Foundations

In modern parlance, Cecil was a workaholic. He worked by day and night, writing the vast majority of his letters in his own hand, and working out arguments by creating long lists of pros and cons. But even the busiest man needs some outlet for his creative energies, and Cecil’s artistic bent found its expression in architecture. Architecture was one of the most fashionable pursuits of gentlemen in the Renaissance period – it was used to express power and wealth as well as taste and education, and there is no doubt Cecil wanted to indicate that he possessed all of those attributes.

During his long life and political career, Cecil built three vast properties that typified the Elizabethan style. Sadly, only one remains - Burghley House. The other two, Cecil House on the Strand, London, and Theobalds (bizarrely, pronounced Tibbalds), near Cheshunt, in Hertfordshire, just north of London, have left no traces. Nevertheless, from the copious records kept we can learn a bit about them. He also built or renovated two other houses – one named Pymmes at Edmonton (not far from Theobalds) and one at Chelsea, in London, although we cannot find any direct evidence of ownership or any reason for him to have a property there..

Architecture was a taste that Cecil first seems to have developed during Edward VI’s reign. His patron, the Duke of Somerset, built the vast Somerset House in the Strand – the first great construction by a subject since Wolsey had created Hampton Court, some thirty years before. Whilst he was Somerset’s Master of Requests, it is likely that Cecil visited frequently, and, it appears he was impressed by it, as the West Gate he built at Burghley resembled the earlier construction.

Other members of Somerset’s household who were friends of Cecil’s were Sir Thomas Smith and Sir John Thynne, builders of Hill Hall, Essex (now owned by English Heritage) and Longleat, in Wiltshire, respectively. Longleat, currently lived in by a descendant of Thynne, is similar in style to Burghley House, and we can speculate that Cecil and Thynne conferred.

The fall of Somerset did not put an end to architectural discussion at court – the Duke of Northumberland was also interested in the practice, and sent John Shute, author of the first English treatise on architecture, to Italy. Doubtless Cecil was fascinated by what Shute discovered there and would have read Shute’s work - The First and Chief Grounds of Architecture.

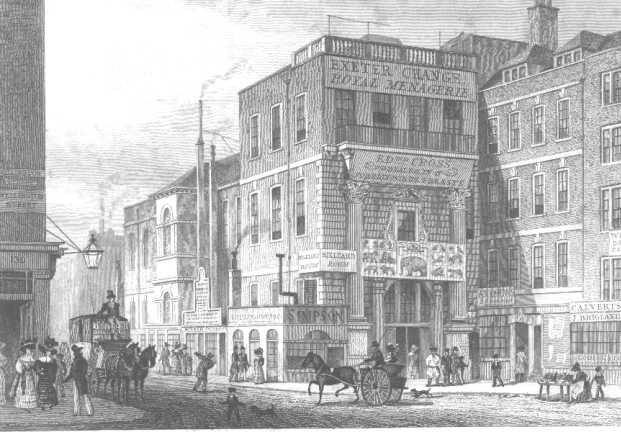

As well as Somerset House and Longleat, another model for Burghley was Sir Thomas Gresham’s new Exchange, in the City of London, the stone loggia (an open arcade) of which was originally copied at Burghley, although it was later covered in.

Construction

According to his early biographer, the Rev. W.B Charlton, who was chaplain to the Marquess of Exeter in the 1840s, Cecil’s father, Richard, was granted the former priory of St Michael’s, Stamford together with 299 acres of arable land in 1539. This became the nucleus of the modern Burghley estate, and Cecil began working on it after his father’s death in 1553. It remained the principal house of his mother, Jane, until her death in 1588. The original works, carried out in the 1550s and 1560s, were later replaced with even grander edifices.

Cecil’s great masterpiece was Theobalds. He acquired the land, just west off what is now the A10 some time around 1560. He probably chose the location as handy for travelling between Cecil House in the Strand, and Burghley. Information about one of his journeys between his previous house in Wimbledon and Burghley show that this is the route he customarily took.

Major works seem to have begun in the late 1560s – in 1572 alone, he spent £2,700. The property was finally finished in 1585. There are some 18 drawings still extant in the archives at Hatfield House (which Cecil’s son, Sir Robert, acquired in exchange for Theobalds when James VI & I made clear his desire to own the great pleasure palace himself). From the annotations on the drawings, it can be inferred that Cecil himself was, at least in part, his own architect and designer. He appears to have been able to draw well – there is a note from a mason at building asking him to send a detailed drawing, so that he can understand what is required.

Once completed, the house was vast – set around five courtyards, with two large courtyards or quadrangles, and smaller ones for the buttery, the dial (clock) and the dovecotes. The domestic parts of the building surrounded the dovecotes. There were also long galleries and a great hall.

The one of the main quadrangles, Fountain Court, was 86 ft square and housed a water feature of black and white marble. On the east of the court was an open loggia, floored with Purbeck marble, presumably for walking in to catch the evening sun.

Residence

The location made Theobalds a convenient place for Elizabeth I to travel to when she wished to leave London for a spot of hunting. She paid him repeated visits over the years, the first being in 1564, when she apparently complained that her bedroom was too small, leading him, or so he claimed, to enlarge the house. It was still not complete by the time she arrived again on 22nd September 1571. Rather than the Queen bringing a gift with her for her hostess, she was the recipient of some verses (one’s ears cringe at the thought) and a picture of the house.

Whether it was the house or the company she most enjoyed, she visited again in 1572, 1575, 1577, 1583, 1587, 1591, 1593, 1594 and 1596.

Sometimes her stay was of brief duration, but on other occasions she brought a large retinue with her. Elizabeth, perennially short of money, and of a thrifty turn of mind, was always happy for her courtiers to support some of the financial burden of the court. In 1583, she was accompanied by her friend, Robert, Earl of Leicester; his brother, the Earl of Warwick; her other favourite, Sir Christopher Hatton; Cecil’s companion and colleague, Sir Francis Walsingham; the Queen’s cousin, Lord Hunsdon, and several others.

Ten years later, she visited for nine days at a cost to Cecil (who was also of a frugal nature, and must have wilted under the bills) of nearly £3,000. With such sumptuous hospitality available, it was not unknown for Elizabeth to invite foreign ambassadors and dignitaries to wait upon her at Theobalds – the house and gardens were beautiful, and Cecil was picking up the tab!

To give this sum some context, his usual weekly bills at Theobalds were around £80 and his annual stabling bill was about £667. He paid £10 per week for the local unemployed to work in the gardens, and distributed £1 per week in charity. According to custom, even when Cecil was not in residence himself, there was provision for a table of gentleman and two tables of ‘inferior’ persons for dinner each day. His silver plate weighed some 14,000 pounds (c. 6,350kg).

One of Cecil’s favourite recreations was to ride around his gardens at Theobalds, on a mule.

Elizabeth would also visit Cecil at his town house, dining there on at least one occasion and attending the christening of his daughter, Elizabeth, to whom she stood as godmother. Cecil House, of which no trace now remains, was located on the Strand, north of where the Savoy Theatre now stands. It was built of brick, with four turrets and two courtyards. On the east range were the family’s private apartments. To the north, the gardens stretched as far as what is now Covent Garden.

Cecil’s interest in building presumably led to his appointment as Overseer of the Queen’s Majesty’s Works in 1572, although his job was probably to oversee the finances. The comptroller of the Works, from 1556 – 1596 was one Thomas Fowler, with whom Cecil was on good terms, as may be inferred from the fact that Fowler bequeathed his house to Cecil, should he wish to accept it. Other men within the office were Thomas Graves, Surveyor of the Queen’s Works from 1578, Henry Hawthorn and John Symonds; drawings from the men remain in the archive at Hatfield. Graves seems to have worked for Cecil on the manor house at Pymmes, which Cecil purchased in 1582, paying £250 for six acres of pasture and a manor house. Once completed, it was lived in, after his marriage, by Cecil’s younger son, Robert.