Thomas Wolsey: Life Story

Chapter 9 : Difficult Times (1522-1525)

The failure of the peace talks at Calais, whether or not Wolsey had been sincere, and the Treaty of Bruges made with Charles, meant that England was now, once more, committed to war to the tune of 40,000 men and horse, plus a fleet. Henry was delighted with Wolsey, sending letters in which he

"thanked God [he had] such a chaplain by whose wisdom fidelity and labour [he] could obtain greater acquisitions than all [his] progenitors were able to accomplish with all their numerous wars and battles."

The talks with Charles were followed up by a state visit by the Emperor, which, again, Wolsey was responsible for arranging. Whilst not on the scale of the Field of Cloth of Gold, it was still impressive. It was agreed between the monarchs that any disagreement would be arbitrated by Wolsey. Charles must have been grinding his teeth, but the prospect of obtaining England through marriage, and achieving his ancestors' goal of completely encircling France presumably made it worth his while to accept the dominance of Henry's cardinal.

Henry might have been excited at the prospect of renewed war, but Parliament was not. There was no alternative to calling Parliament – the anticipated costs of the campaign were nearly £400,000. A Commission had been sent out in March 1522 to assess the taxable worth of land, houses and valuables, and the City of London had been "persuaded" to offer a loan of £20,000, but this was nowhere near adequate.

Parliament was called in April 1523. Wolsey, as Lord Chancellor, explained Henry's need for money, emphasising the treachery of the old enemy, France. He then asked for the unbelievable sum of £800,000, equivalent to a 20% tax across the board.

The Speaker of the Commons, Sir Thomas More, urged obedience to the King, but the Commons could not accept the demand. They asked Wolsey to request the King to take less, but Wolsey treated them roughly and refused to countenance such an idea. He then went to Parliament in his full glory, robed in red, with his Cardinal's hat and his Lord Chancellor's Seal, to intimidate the Commons. The House sat in silence, neither refusing, agreeing nor debating. Eventually, humiliated, the Cardinal left.

At last, a subsidy of 10% was voted, but there were murmurings across the country. Wolsey augmented the grant with a massive levy of 50% of a year's income on the Church, which he forced through as Legate, overriding Warham.

Despite the pain involved in raising the funds, the campaign of 1522-23 was a shambles. Unlike in 1513 when the English army had been considered a model of good behaviour, the campaign was largely about desecrating and laying waste the French countryside. Eventually, bogged down by the rain and mud of northern France, as every army in European history has been, the commander, the Earl of Surrey, withdrew to Calais, to await a further advance in 1523 under the Duke of Suffolk.

Suffolk too, after initial promising gains failed to make any serious progress. The appalling conditions " which caused the soldiers daily to die" led to him advocate a retreat, but Henry was adamant. Wolsey had interfered in military matters and should have borne some of the responsibility for the fiasco, but Henry appears to have heaped all the blame on Suffolk. Suffolk may have owed Wolsey a favour for helping him when in disgrace over his marriage, but this reverse wiped out all gratitude and pushed Suffolk firmly into the growing camp of Wolsey's enemies.

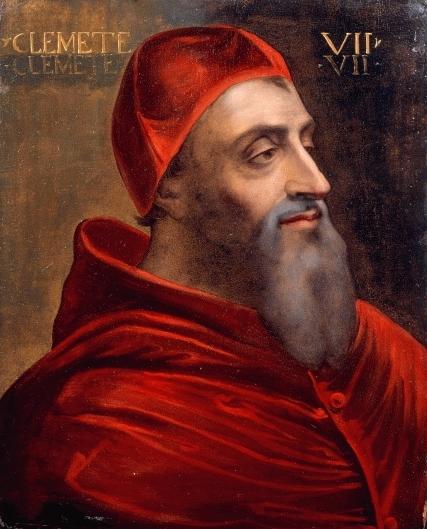

By 1524, the failure of Charles to keep his side of the bargain, and the exhortations of the new Pope, Clement VII, for peace, inclined England to begin making overtures towards France again. Francois was not particularly interested in coming to terms – his sights were firmly on Italy. He crossed the Alps, heading for his Duchy of Milan, secured nine years earlier at Marignano. This time, however, it was the Emperor's turn for glory. On Charles V's birthday, 24 February 1525, the Spanish-Imperial army won a crushing victory at Pavia, taking Francois prisoner and annihilating his army.

Back in England, Henry was initially delighted, jumping out of bed to run to his wife and share the good news. Now would be the time for Charles and him to dismember France. Soon enough, though, it became apparent that Charles had no more interest in helping Henry to the French Crown than his grandfathers, Ferdinand and Maximilian had had. Moreover, he no longer needed the English alliance to be cemented by his marriage to Henry's daughter.

Henry, still keen to press the advantage of a France in turmoil proposed to lead yet another invasion. The question was how to fund it. There was no hope of Parliament voting another subsidy, so Wolsey hit on the idea of a loan, the "Amicable Grant", based on the feudal prerogative of the King being "aided" with money if he led an army abroad in person. The idea was no doubt taken up with glee by the King and Council, but the result was a miserable failure. Despite bullying in person by Wolsey, London refused to cough up. In the provinces, the Commissioners sent to collect it (including Sir Thomas Boleyn) were manhandled. East Anglia was close to open rebellion.

Henry, seriously worried, cancelled the grant. He was not pleased with Wolsey. Not pleased at all.

Troubles came thick and fast as the Emperor came to terms with France, and, in the Treaty of Madrid allowed Francois to return home, with a new wife (Charles' sister) but minus a huge sum of cash, and his two sons, who were sent to Spain as sureties. Charles also calmly announced that he would not be marrying Princess Mary after all, but would seek a bride from wealthy Portugal. The rest of Europe was now horrified at Charles' overwhelming strength, and united in the Treaty of The More, negotiated again by Wolsey and signed on 30 August 1525 at his home.